Paying For It

Future Cash Flow

The vast majority of the project is paying upfront for wind and solar and then future cash flow can pay off incurred debt. Any extra tax needed will be relatively minor.

The federal government is able to borrow money at low interest rates and has a tax base that is consistently growing meaning new debt sits around like a 0-interest loan.

The government, or whoever owns the solar and wind energy production, can pay off most of the debt over decades.

Example 1: The utilities will cost much less to operate under renewables so if your utility bill stays the same there is a difference in cash flow to pay whoever borrowed to put in the renewable energy (the government is the best borrower).

Example 2: The energy to operate and maintain electric vehicles is much less. You could increase registration fees to pay for climate capital costs and the vehicle maintenance would still be lower than typical combustion engine gasoline and maintenance.

Taxes

This is not the place for a long economic discussion, but this author hopes we continue to think big about our values, our tax system, and be bold to have opinions on our labor or we will be beholden forever to the tides of wealth concentration and aversion to change and thought.

Our current debt is also our wealth. Some is owed outside our borders but individuals here also own a lot of foreign debt. The net result is minor. If we want to decrease debt and create more opportunity while not increasing labor hours, some wealth has to go down. If the stock market goes down but GDP doesn’t, then either the market is cheaper for the next person or less of a share of labor is being syphoned off for corporate profits. There are winners during a market downturn and there is more opportunity.

Taxes are basically a way to move labor to something (military, seniors, healthcare, environment, etc.) without promising future labor in the form of a bond. It does not make us less poor, but rather maintains opportunity as future labor is now not obliged to a debt. Spending can create a burden for labor but taxing does not.

If tomorrow we decided we didn’t want a military, which is about 4% of the GDP we could all work 4% less or consume 4% more. If we decide to increase spending a trillion dollars a year on a value with no return on it we absolutely could. That is about 5% of the economy so on average we would be consuming 5% less or work 5% more.

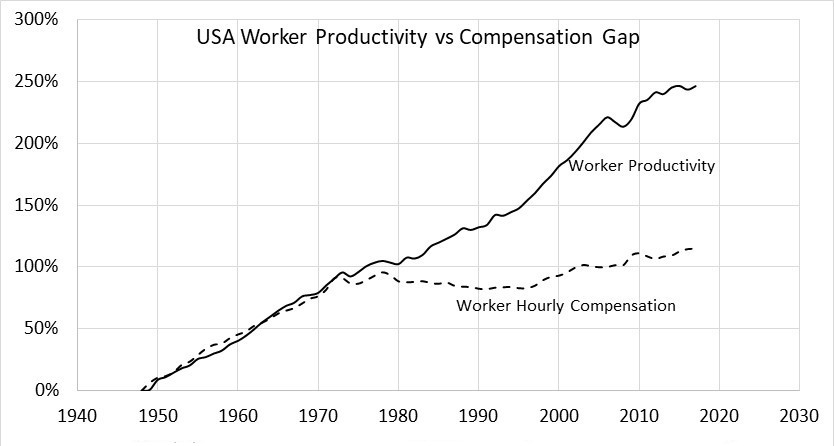

There is also the growth and inequality part of the equation. Without intervention from the government or unions, economic growth from increased productivity goes to the top, so naturally many will want to go after the money at the top for any pay for instead of a flat X% increase across the board.

This is not the place for a long economic discussion, but this author hopes we continue to think big about our values, our tax system, and be bold to have opinions on our labor.

Example of World War 2

During World War II up to 40% of the economy was directed to the war effort. Factories all over were converted to war needs, women were put into the workforce, rationing went into effect, taxes were high etc. We can direct the economy in large ways when motivated. 40% of the economy would be equivalent to $8 Trillion in annual labor today in the United States! The economy doesn’t care if it is making tanks or solar panels or a major health initiative or large infrastructure or giant pyramid tombs for its leaders. These are all forms of labor.

Carbon Tax

A carbon tax will make sense in the future as fossil fuels will continue to be used and the Earth can handle some emissions, but society will not want them to be the cheapest option. Revenue from a carbon tax means taxes can be less somewhere else. Jollies and security associated with fossil fuels will continue in the future.

References

- Economic Policy Institute. The gap between productivity and a typical worker’s compensation has increased dramatically since 1979. https://www.epi.org/productivity-pay-gap/. Accessed January 15, 2020.